'Concern - Hope - Answer'

liquid Waste Management Conclave in Kerala - An overview

Kerala’s dedication to human resource development and a decentralized governance model has earned it widespread recognition, resulting in a significant enhancement of living standards across the board. This improvement is particularly evident in the domains of public health, clean drinking water access, and sanitation, where Kerala has outperformed many other states in the country. Remarkably, Kerala has already achieved success in eradicating open defecation and manual scavenging, setting it apart from ongoing efforts in other regions. However, the state now confronts a fresh challenge in the management of toilet waste.

Kerala’s urbanization pattern is unique, characterized by a seamless blend of rural and urban areas, often referred to as urban agglomerations. This distinctive feature, coupled with Kerala’s rich ecological and cultural diversity, presents a formidable challenge when it comes to devising effective technologies and approaches for managing liquid waste. The conventional centralized systems commonly employed for liquid waste treatment may not align with Kerala’s distinctive context. It’s evident that a “one-size-fits-all” model cannot adequately cater to the region’s intricate nuances, nor can it address the specificities of local bodies.

To address this issue, the Suchithwa Mission, the government’s nodal agency in the waste management, organised the GEX KERALA ’23’ conclave. The objective of this conclave was to develop liquid waste management (LWM) solutions suitable for Kerala through local bodies by understanding the modern and scientific methods. The conclave brought together various government agencies in waste management, including Haritha Kerala Mission, Clean Kerala Company, Kerala Solid Waste Management Project, to explore innovative solutions for the state’s waste management challenges.

In this blog, we will examine the approach adopted by the Suchithwa Mission in this conclave, the challenges and opportunities presented by Kerala’s decentralised structure, and the potential solutions to the state’s unique waste management problems.

Awarness, Perspective, Knowledge

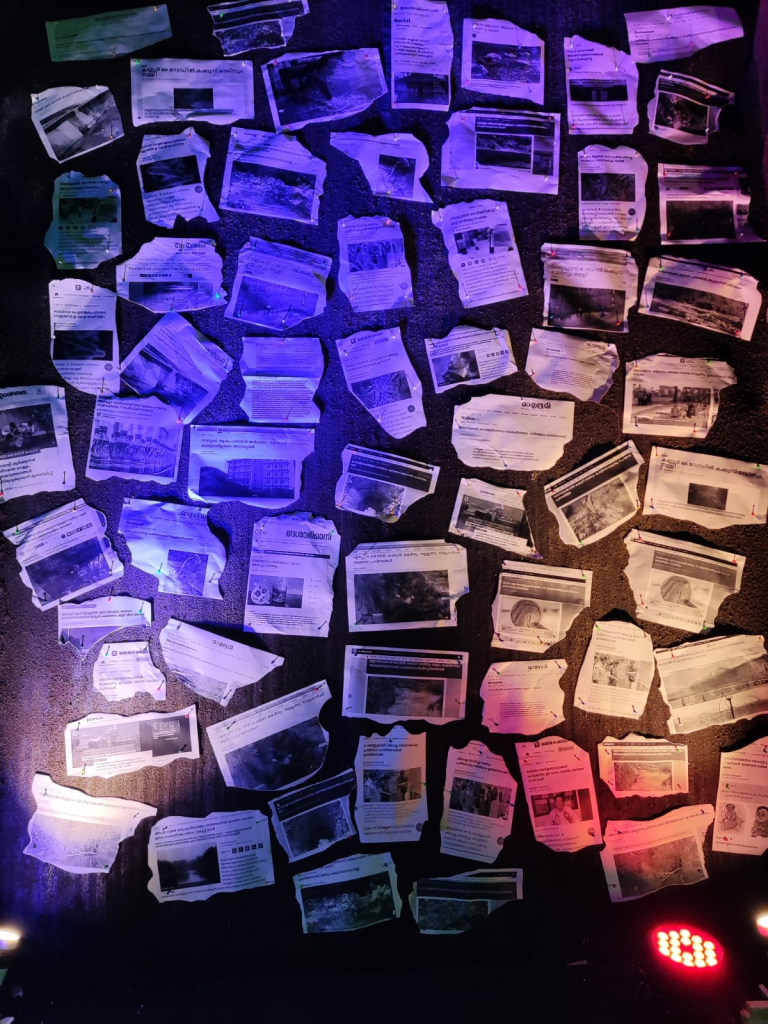

Divided into three parts, the first part of the conclave included an exhibition, a knowledge hub, and a perspective stall. The exhibition showcased a range of technologies for LWM, such as centralized-decentralized, nature-based, technology-based, simple, and complex. The knowledge hub aimed to convince local governments of the importance of LWM and formulate a basic vision. At the same time, the perspective stall helped local governments gather perspective and choose appropriate technologies based on their environmental, social, and cultural contexts.

The conclave emphasised the circularity of waste as a general perspective on LWM. Urbanisation has disrupted the natural cycle of water and nutrients, resulting in harmful side effects such as the pollution of water bodies, morbidity, and pathogens in drinking water. To restore the circularity of the water-nutrient cycle, the conclave introduced the fecal sludge value chain approach, which involves treating toilet waste in stages and recovering its nutrients to restore soil fertility in agricultural fields. While this network cannot be established and maintained within a single local government body, each local government can intervene in each value chain link to solve their waste problems and restore the natural cycle of water and nutrients.

Peer Learning and Co- creation of knowledge

The importance of peer learning and knowledge co-creation in addressing the LWM problem in Kerala was highlighted in the conclave. Every local government body in Kerala has unique and innovative ideas for addressing local problems. For example, Alappuzha Municipality developed a decentralised solid waste management program that was later widely implemented in Kerala. Other innovative ideas include the local drinking water project developed by Olavanna Gram Panchayat, the wetland management program developed by Karakulam Gram Panchayat, and the carbon neutral project developed by Meenangadi Gram Panchayat.

The LWM problem in Kerala is complex and requires innovative solutions that address different dimensions of the problem. Peer learning and knowledge co-creation can help local government bodies in Kerala develop practical and effective solutions to address the problem.

Translation of knowledge into solution, appropriate technology, Technology dissemination

To effectively address the challenges of waste management in Kerala, it is essential to translate knowledge into solutions suitable for the context. However, most technologies available today have been developed for industries or Western contexts, raising uncertainty about their suitability for Kerala. Promoting indigenous technologies and customising existing technologies will be required to overcome this challenge. This cannot be achieved through the technical institutions available in Kerala alone, as there are around 940 local government bodies, each with its own unique background.

Kerala’s startup ecosystem can play a significant role in building technology, making the service available to all local government institutions, and implementing their maintenance and monitoring. By utilising the capacity of technology professionals available in large numbers, Kerala can build knowledge in a highly decentralised manner and translate it into technologies. The Innovators Forum, Hackathon, Entrepreneur Meet, Startup Meet, and other similar initiatives can be used to promote this approach.

This approach will not only benefit educated professionals and the local community by creating job opportunities, but it will also help reduce dependence on global consultancies in knowledge creation and application. Ultimately, translating knowledge into appropriate technology and its dissemination across the state will be crucial for sustainable waste management in Kerala.

Discussion

The success of the LWM conclave depends on the planning and clarity of the concept and its effective communication to the people. The preconceptions and perspectives of the people towards LWM are crucial as they will impact the implementation of the technologies. The conclave should not be reduced to a technology marketplace for consultants selling technologies. It is doubtful whether the three-day expo can achieve all the visions mentioned.

The National Green Tribunal’s pressure on the state government to plan and implement LWM programs at a fast pace is still there. The state government must plan and implement sustainable waste management solutions suitable for Kerala.

The conclave can be considered an important step in constructing a larger vision for waste management in Kerala, but sustained efforts are required to develop these solutions. The Suchithwa Mission should direct and nurture the professional-startup ecosystems in Kerala to study the situation of local governments, build technologies suitable for each region, and provide service providers for local governments. New strategies for awareness raising, perspective gathering, and capacity building should also be devised and reach out to local government institutions in greater depth.