Reclaiming our environment from the clutches of plastic- decoding EPR to transition to a Circular Economy

The quality of our lives depends on the quality of our environment. A recent study confirmed this seemingly obvious correlation – when your commons are clean and you have good quality air and water, with clean lakes and canals and green spaces around you, your life satisfaction improves.

While this may seem a no-brainer, it seems to be an elusive idea to execute. What else explains the floating plastic and litter in the scores of water bodies in the country? Vembanad Lake, a tourist hotspot in the Alleppey Kottayam belt, is also a plastic waste hotspot with microplastics detected in lake sediments.

Microplastics have been linked to multiple impacts on human health, ecosystem health, and the environment. And the only way to stop microplastic pollution? Responsible management of plastic.

India generates 26000 tonnes of plastic waste every day. Out of this, only 8% of this plastic is recycled, 29% is mismanaged, and the rest is incinerated or dumped, finding its way into water bodies such as the Vembanad Lake.

To tackle the global menace of plastics, the United Nations has committed to deliver a legally binding Plastics Treaty agreement by the end of 2024. Once this comes into force. nations will be bound to enforce strategies to tackle plastic pollution and enforce responsible management and disposal of plastic.

Some nations already have an action plan in place. And one of the major tools in their arsenal is the Extended Producer responsibility program. Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Singapore have a well-established EPR framework for products such as packaging, electronic items, and home appliances.

India is not far behind, EPR regulations were first introduced in India in 2012 to focus on e-waste and were extended to plastic waste in 2016. However, with limited data on the types and fate of plastic waste and with no recognition of the huge informal network that manages the bulk of the generated waste, EPR in its current form can do little in the country.

Demystifying the current EPR regime in India

The EPR regime in India is primarily governed by Plastic Waste Management Rules 2016, its subsequent amendments and guidelines, and policies released by the Central Pollution Control Board and different states. These policies confer some responsibilities or liabilities on each of the stakeholders involved in the plastic supply, use, and disposal chain. To understand why EPR is not working in India, let’s look at the liabilities of each of these stakeholders and why they cannot fulfill them.

The first and probably the most important of the stakeholders are the Producers, Importers, and Brand Owners (PIBOs). According to EPR policies, they are responsible for setting up a system for collecting back and recycling the plastic waste generated due to their products. Further, they are required to achieve specific collection and recycling targets. While PIBOs can do this individually, this responsibility is capital and resource-intensive. Hence many times it is outsourced to other organizations known as Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO).

The second responsibility of PIBOs is to register themselves with CPCB and SPCB along with submitting an EPR action plan. This plan must detail the strategies for the collection, transportation, and processing of plastic waste. And lastly, they must also maintain detailed records – the amount of plastic waste generated due to their products, and how much of it was collected and recycled and submit the same to CPCB/SPCB. PIBOs bear the financial cost of fulfilling all these responsibilities.

Coming to Producer responsibility organizations, one of the most critical players involved in the implementation of EPR guidelines in India. Once PIBOs outsource their responsibilities to PROs, the latter must ensure that PIBOs fulfill their EPR obligations. Just like PIBOs, they must also register with CPCB and SPCBs and maintain detailed records of their activities. PROs are responsible for establishing systems and mechanisms for the collection, transportation, and processing of plastic waste. They can either establish infrastructure for carrying out these tasks or collaborate with ULBs.

ULBs have a dual liability under the EPR regime. On one hand, they have to create and maintain infrastructure for plastic waste segregation, collection, and processing within their jurisdictions, and on the other, they are also tasked with monitoring and enforcement of compliance by PIBOs and PROs. The task of monitoring and compliance also falls under regulatory agencies CPCB and SPCBs. CPCB is involved in national-level policy making and drafting of guidelines while SPCB handles implementation and monitoring and enforcement to ensure compliance.

What ails the EPR regime in India?

Now that we know what the responsibility of each of the stakeholders is, let’s look at the challenges of the EPR regime.

Huge financial implications

Establishing an EPR system and processes is a costly affair. It takes a fair amount of capital and resources. And while large companies can either do it individually or outsource it to PROs, smaller firms cannot afford the same. Moreover, a competitive market means that producers cannot externalize this cost to consumers. Thus there is no incentive for them to comply with EPR regulations. Further, establishing recycling units is a capital-intensive process. PIBOs, PROs, and informal recyclers face financial challenges in setting up this infrastructure.

Weak Enforcement Mechanisms

Not only do the PIBOs have no incentive, there are often no sanctions/penalties for not establishing EPR systems. This is because they often escape the scrutiny of regulatory agencies. Plagued with limited staff and low resources, central and state pollution control boards cannot adequately perform their duties of monitoring and auditing of EPR compliance.

Operational Challenges

Even if PIBOs are interested in adhering to EPR policies and guidelines, they may face operational challenges such as a lack of infrastructure and inefficient waste management practices. ULBs, who are the main stakeholders responsible for creating infrastructure are often understaffed, and lack resources. Now what happens if they do create infrastructure using government schemes or through private participation? They eventually fall into disuse as many ULBS find it difficult to maintain them. Lack of infrastructure is also applicable to recyclers, especially for the flexible plastic packaging category

Another reason for the failure of such formal mechanisms is that there is a considerable number of informal players – waste collectors, sorters, and recyclers who are involved in waste management in the country. To improve operational efficiency, it is crucial to integrate them into the formal system. Needless to say, this process of formalization will give legitimacy to them and honor the critical service they are rendering. Formally recognizing them will also give them access to financing channels such as banks to raise capital and establish efficient recycling systems.

Logistical and technical issues

Many times the supply chain of a product becomes complex and fragmented. With many of the intermediate players in the supply chain using generic packaging materials, it becomes difficult to track the origin and fate of the disposal of each piece of plastic. There is also the issue of the sheer range of plastic products and materials. Even if they are collected and segregated, each category requires a specific tailormade process for recycling.

Lack of awareness and education

Segregation of waste is the most important step for the success of any EPR scheme, and one of the causes for this is the lack of awareness at the end of consumers. On the other hand, lack of awareness at the end of PIBOs and PROs can also lead to sub-optimal implementation of EPR as it leads to their non-compliance with EPR obligations. Most often it is small businesses and MSMEs, who are unfamiliar with relevant EPR policies and guidelines.

Lack of data

Maintaining granular and detailed data logs on the material flow of plastic – who produced how much, where and how is it used and how is it being disposed of is critical for the successful implementation of EPR. While ‘who produced how much’ can be known from the PIBOs and PROs (from the EPR dashboard), the second and third data points are much more tricky to discern. With many of the ULBs depending on informal networks for waste management, they do not have information on the total amount of waste generated within their jurisdiction. A considerable quantity also ends up in streets, water bodies, and oceans.

Is EPR the only way to tackle plastics?

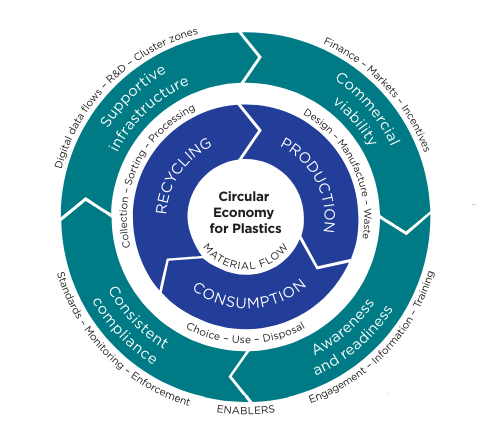

Not really, EPR is one of the tools in the arsenal to address plastic pollution. Recently there has been a focus on the need to transition to circular economy for plastics. Some countries have also developed roadmaps and visions to guide their transition towards sustainable consumption through a circular economy. Japan has Circular Economy Vision which integrates various policies and strategies to promote circular vision models. Similarly, Indonesia has a Waste Reduction Roadmap which mandates producers in the manufacturing, food and beverage, and retail sectors to reduce and manage their waste. This plan goes much beyond EPR, by requiring producers to reduce waste at each stage of their process cycle and by phasing out non-environmentally friendly materials through material substitutions and bans.

India’s own Roadmap to circular economy – the National Circular Economy Roadmap for reduction of Plastic waste in India is an exciting vision document. A transition to a circular economy means that clear mechanisms will be set in place to extend the use of plastic materials, collect waste and end-of-life plastic, and recycle it for its next use. The roadmap spells clear recommendations for creating a conducive policy and institutional environment for enabling a circular economy.

One of the most critical elements in India’s Circular Economy Roadmap is Supportive Infrastructure. Infrastructure means not only physical hubs where collection and processing of plastic take place but also a fine-grained digital dashboard on the material flow of plastic – from PIBOs through to re-use, secondary processing, and disposal. The vision document envisages the establishment of Digital platforms in place for data collection and reporting by 2035.

Collaboration - for effective EPR and transition to a Circular economy

In executing EPR as well as in transitioning to a circular economy, what is critical is the need for data. To empower the thinly staffed and resource-starved municipalities and ULBs in collecting and maintaining data on plastics, we need a collaborative effort involving municipalities, producers, and consumers. By leveraging open-source technologies, encouraging public-private partnerships, and harnessing the power of communities, it is possible to support local governments. Only by fostering a culture of collaboration and innovation can we make significant strides in reclaiming our environment from the clutches of plastic.

Author