Sustenance of Vembanad Lake Through Innovative Governance Models

Vembanad Lake, one of India’s most significant natural resources and a designated Ramsar site, is grappling with severe pollution from multiple sources. Alongside the persistent problems of industrial waste and agricultural runoff, the lake now faces additional threats from rapid urbanization and the burgeoning tourism industry. Kerala, the state where Vembanad is located, is undergoing swift urban development and an economic boom driven by tourism. Unfortunately, the existing governance structures in Kerala are ill-equipped to manage these emerging challenges, underscoring the urgent need for effective governance models.

In response, the CANALPY initiative, launched by IIT Bombay and the Kerala Institute of Local Administration (KILA), with backing from the Duleep Matthai Nature Conservation Trust has developed an approach aimed at revitalizing the canal commons in Alleppey town, which is under significant strain from urbanization.

This blog delves into the potential of replicating the CANALPY approach to the broader context of Vembanad Lake, particularly focusing on the stretch between Thanneermukkam Bund and Thottapalli Spillway. This area is heavily impacted by urbanization and large-scale tourism. By enhancing the governance system’s capacity to manage natural resources amidst rapid urbanization and expanding tourism, the goal is to develop a model that can be applied not only in Kerala but also in other rapidly urbanizing regions facing similar challenges.

Overview of Vembanad Lake

Vembanad Lake is a significant part of the larger Vembanad wetland complex, the largest in Southwest India, spanning an area of 2,033 km² with a length of 96 km. This dynamic wetland complex comprises backwaters, marshes, swamps, paddy fields, brownfields, and estuarine areas. The larger wetland complex is fed by ten rivers—Keecheri, Puzhakal, Karuvannur, Chalakudy, Periyar, Moovatupuzha, Meenachil, Manimala, Pampa, and Achankovil—which converge into Vembanad from the south of Alleppey to Azhikode. Collectively, the catchment area of these rivers and Vembanad covers approximately 16,200 km², constituting about 40% of Kerala’s total area.

The watershed is divided into two distinct arms based on land elevation and water circulation patterns. The northern arm, a relatively shallow and narrow 30 km stretch, extends from Kochi to Azhikode. The southern arm, a deeper and wider 62 km region, runs from Kochi to Alleppey. Approximately 40 km from Kochi, at Thanneermukkam, the southern arm is divided by a bund. North of this bund lies the Vaikom Kayal, while the expansive area to the south, extending to Kainkari, is known as Vembanad Kayal or Vembanad Lake. This area varies in width from 500 meters to 4 km and in depth from 1 meter to 12 meters.

Vembanad Lake traverses the districts of Alleppey and Kottayam and is fed by the Meenachil, Achankovil, Pampa, and Manimala rivers. The lake is vital both economically and ecologically, supporting approximately 1.6 million people through agriculture and tourism. Ecologically, Vembanad Lake is recognized as a Ramsar site and is included in the National Wetlands Conservation Program. It hosts 150 fish species and numerous migratory birds at the Kumarakom Bird Sanctuary. The lake’s wetlands also support diverse mangrove species and the unique ecosystem of Kuttanad, enhancing its rich biodiversity and making it a critical area for conservation.

Pollution Threats and Impacts

Vembanad Lake is under considerable threat from various pollution sources. Industrial effluents contribute to 60% of the pollution load (Kumar et al., 2017), with agricultural runoff increasing by 150% over the last two decades (Kerala State Pollution Control Board, 2021). Untreated domestic sewage, accounting for 40% of the pollution (CWRDM), and waste from tourism activities further compound the problem. These pollutants exacerbate eutrophication, leading to nutrient overloads that fuel algal blooms, disrupting the ecosystem balance (Kerala State Pollution Control Board, 2021).

The pollution in Vembanad Lake has had a devastating impact on its flora and fauna. Since 1993, the bird population has declined by 40%, with migratory ducks ceasing to roost in the area (Vembanad Water Bird Count 2003). Fragmentation of mangroves, coupled with excessive nutrient input, has led to algal blooms that choke native plant species and disrupt the aquatic food chain (Kerala State Pollution Control Board, 2021). Heavy metals from industrial effluents accumulate in the tissues of fish and other aquatic organisms, posing significant health risks (Kumar et al., 2017). Overfishing has further led to a 30% decline in fish catch rates, affecting the livelihoods of over 50,000 fishermen (ICAR, 2017).

Human interventions such as the Thanneermukkom bund and Thottappally spillway, originally intended for flood control and salinity management to boost agricultural productivity, have inadvertently caused water stagnation. This stagnation leads to the accumulation of pollutants, further degrading water quality and exacerbating the ecological imbalance.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, reduced human activities led to significant improvements in water quality, highlighting the impact of human activity on the lake’s health. The pollution from neighbouring settlements and tourism hubs, particularly houseboats discharging sewage, remains a major concern, leading to high coliform bacteria levels and ecological damage (New Indian Express, 2022). Studies have also highlighted extensive microplastic contamination, emphasizing the need for better waste management (Asianet Newsable, 2018). Efforts by authorities, including the National Green Tribunal and Supreme Court, aim to address pollution through measures such as the demolition of illegal constructions and stricter environmental regulations.

Student-citizens for small towns in India

One student-citizen, who religiously participates in the schools and campaigns talks about having her roots in Alappuzha that helped her to retain interest in the process. She excitedly talks about meeting other students coming from various disciplines with multiple perspectives contributing to each other’s work, producing knowledge together. During the campaigns, she wrote press releases for the Swap Shop and spent time sorting out clothes, picking out the ones that are fit for reuse. She warmly remembers the comic book that has been designed for children to get them on board. This coming in of student-citizens are relevant for small towns like Alappuzha.

Small towns are becoming greenfield sites for development interventions, yet service and infrastructural deficit remains a characteristic feature of these small towns in India. Student-citizens are capable of addressing the deficits by bringing in the research component which is largely missing in the small towns. The student community also proposes appropriate infrastructural interventions that are feasible.

While everywhere effects of climate change are felt, coastal regions and low-lying areas are especially vulnerable to the rising sea levels. This makes the converging of academic attention through student-citizens particularly important for Alappuzha which is a littoral town. Mounting to this is the increased incidence of urban floods; prolonged water logging and polluted canal waters entering houses being a common occurrence. Local bodies struggle hard to deal with urban floods which are exacerbated by the pressures of urbanization, making student-citizens a much-needed presence in small towns that needs to be sustained.

Emerging urbanisation and its challenges

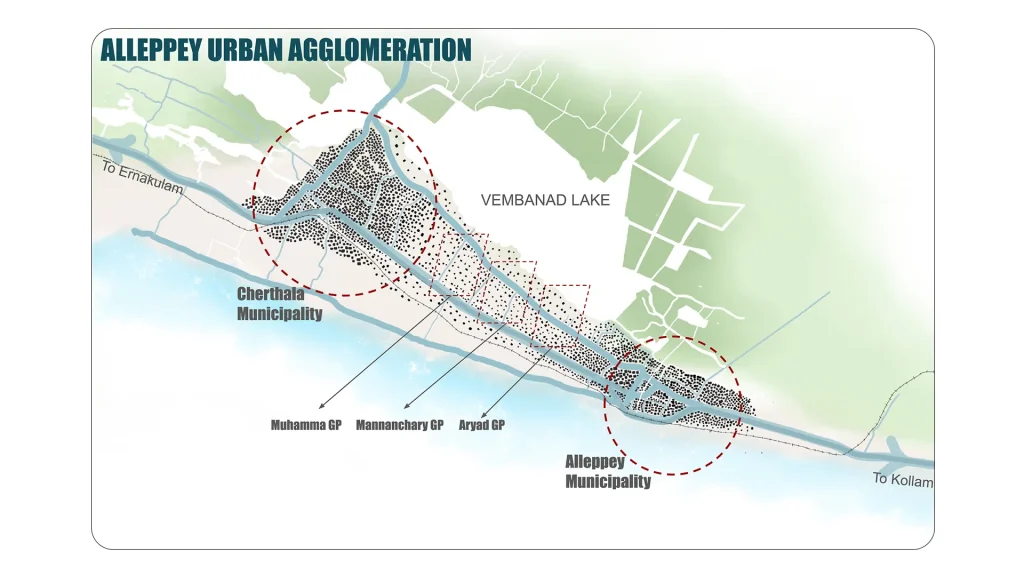

Vembanad Lake, a vital common pool resource, sustains both ecosystem functions and local livelihoods. Addressing pollution challenges is crucial for preserving the lake’s ecological balance and the well-being of dependent communities. The urban agglomeration around Vembanad Lake encompasses the expanding Cherthala and Alleppey municipalities, as well as three intervening panchayats—Muhamma, Mannanchery, and Aryad—projected to form a densely populated area in the future. This region, sharing boundaries with the lake, faces significant impact from urbanization, unlike other parts of the lake with less urban activity. This anticipated urban development is expected to have substantial environmental consequences, including heightened pollution levels and increased challenges in waste management (Kumar et al., 2017). Currently, the Alleppey and Cherthala municipalities, already established as urban areas, are significant contributors to Vembanad Lake’s pollution due to their urban nature. The gram panchayats of Aryad, Mannancherry, and Muhamma, positioned between these urban centres, are comparatively less developed but are likely to urbanise in the future, given their proximity to Alleppey and Cherthala. As a result, the combined pollution from all these areas is poised to significantly impact the ecological health of the Lake. Thus, addressing pollution from these emerging urban areas is essential for ensuring the long-term sustainability of the lake ecosystem and safeguarding its resources for future generations.

Alleppey Model: A Case in Context-Specific Intervention

Previous attempts at pollution management, such as the Ganga Action Plan and Namami Gange projects, have highlighted the inadequacies of mainstream approaches that either focus on centralized treatment systems or rely on bureaucratic command-and-control governance mechanisms. These efforts underscore the need for an alternative approach that integrates context-specific technologies with participatory and inclusive governance mechanisms. This reimagining of pollution management must operationalise the principle of subsidiarity, tailoring infrastructure, policies, and practices to local geographic, political, and socio-economic conditions.

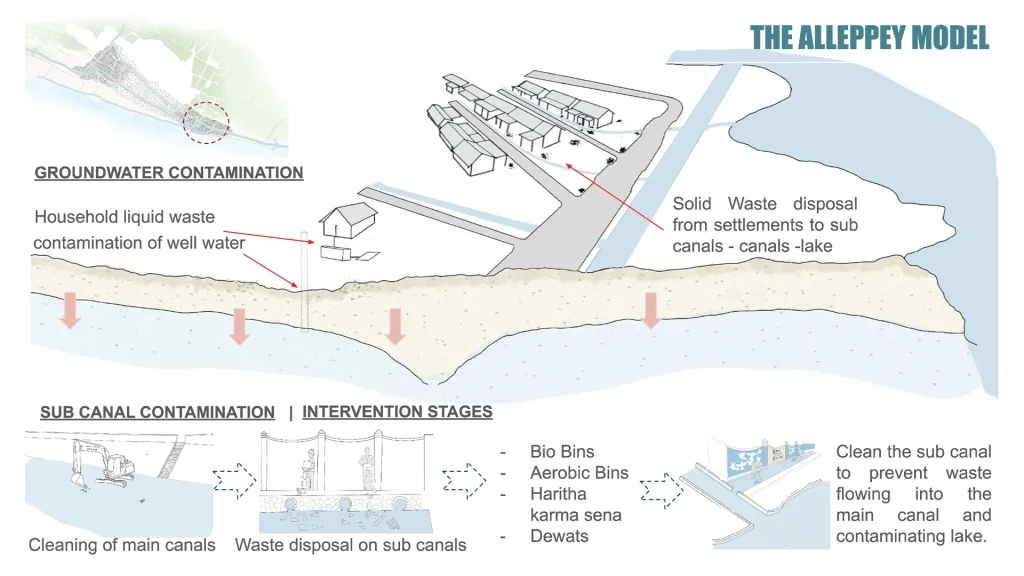

Embracing this perspective, we addressed the pollution of canals in Alleppey by understanding canal degradation not just as a bio-physical failure but also as a governance failure. Poor inter-agency coordination and weak implementation frameworks have hindered effective action. Adaptive governance practices are essential to overcome these challenges. The Alleppey model is a pioneering initiative that aimed to transform not only knowledge production but also technology, operations, and governance.

The CANALPY initiative began with a situational assessment named Winter School 2017, which aimed to understand the town’s sanitation context with the support of local youth, civil society organizations like Kerala Shastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP), and local engineering colleges. Using open-source tools like ODK Collect and OSM Tracker, participants conducted participatory drain mapping, water quality assessments, and household surveys. This process developed a broader understanding of the town’s sanitation practices and waste flows into water bodies.

Building on this, the Summer School 2018 scaled up the efforts, involving over 330 students from technical, planning, and social sciences backgrounds across India. The concept of canal sheds, based on micro wastewater sheds, became the basic unit of planning and intervention. Data collected during surveys revealed the social and spatial aspects of pollution and sanitation practices, leading to the creation of ‘sanitation zones’. These zones help planners identify different sanitation practice typologies and develop context-specific interventions for each locality.

The third activity, Winter School 2018, focused on creating canal shed-specific sanitation plans. The insights from the studies were shared with the local government, Departments of Irrigation, and the Pollution Control Board, along with recommendations for context-specific interventions.

One notable intervention happened in one sanitation zone, the ‘Chathanad Canal shed,’ where an integrated approach to addressing both solid and liquid waste was implemented. This included the introduction of decentralized wastewater treatment systems (DEWATS), door-to-door collection mechanisms, source-level segregation and management of organic waste, and supporting governance arrangements. This region served as a model for scaling up interventions in other sanitation zones and building confidence among governance institutions and the community. Following this several master plans were developed, including a septic tank replacement plan and a town-level solid waste management master plan.

Under the umbrella of a participatory sanitation campaign, ‘Nirmala Bhavanam Nirmala Nagaram 2.0’ (Clean Home — Clean City) aimed at achieving total sanitation, the town achieved substantial progress in solid waste management. The Nirmala Bhavanam Nirmala Nagaram campaign promotes decentralized solid waste management by encouraging segregation and management of waste at the household level. With the slogan ‘My Waste is My Responsibility,’ the initiative ensures that every individual takes responsibility for their own waste, preventing the burden from falling on others.

These three-year efforts culminated in substantial improvements in the quality of the canal systems in Alleppey, demonstrating the effectiveness of context-specific, participatory approaches to pollution management.

Polycentric Governance Approach

With the proliferation of technologies and process innovations, it became clear that improvements were required in the current governance structure to accommodate and sustain these advancements. Equipping the traditional governance system, which faced limitations in meeting emerging challenges, to adapt to new approaches was a necessity. The new governance approach developed in Alleppey institutionalized these interventions and incorporated the public, student community, and civil society into the existing governance system, aligning well with the concept of polycentric governance.

Polycentric governance addresses centralised governance’s limitations by integrating centralized and decentralised features. In Kenya, Baldwin et al. (2015) documented a shift from centralized water governance to a polycentric model due to persistent droughts and violent water conflicts. The centralized, top-down approach hindered communication and adaptation to local conditions, compelling the government to involve local communities in water management.

Similar challenges are evident in Alleppey, where rapid urbanization and frequent floods strain the governance network, primarily managed by the irrigation department and the municipality. These entities, lacking the necessary expertise and coordination, struggled to address canal pollution and structural changes. CANALPY emerged to bridge this gap by engaging diverse stakeholders such as youth, students, households, commercial establishments, and the tourism sector, creating a platform for collaborative governance.

By identifying varied utilities—flood mitigation, environmental sustainability, and tourism—Canalpy recognized conflicting interests, such as waste dumping by households and commercial entities. Addressing these conflicts productively, as suggested by Dietz et al. (2003), Canalpy facilitated a platform for stakeholder collaboration, particularly through student-led initiatives. These initiatives, conducted during summer and winter schools, generated vital knowledge for canal rejuvenation.

CANALPY also collaborates with various stakeholders such as the Health and Irrigation departments, Kerala State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB), Suchitwa Mission, Haritha Kerala Mission, Kudumbashree, COSTFORD, Integrated Rural Technology Centre (IRTC), and local academic institutions. This collaboration creates a space for dialogue, discussion, and knowledge transfer among these entities, often working in silos.

Through networking and liaison efforts, Canalpy has embedded these institutions in a polycentric governance structure. Despite the autonomy of institutions like line departments, Alleppey Municipality, KILA, KSPCB, and academia, CANALPY’s collaborations have created platforms for interactions ranging from cooperation to negotiations. These interactions have resulted in various programs and activities, demonstrating the potential of polycentric governance to manage urban commons effectively.

Extending the Alleppey Model to Vembanad Lake

The approaches developed in Alleppey offer substantial potential for addressing governance constraints around Vembanad Lake in managing the pollution from settlements and enabling context-specific planning. The CANALPY model’s core strength lies in its concept of ‘Sanitation Zones’, which are identified as the optimal units for planning. Each sanitation zone is treated as a microcosm of the larger watershed, targeting pollution at its source and managing smaller watersheds containing lower-order streams that often carry urban garbage and pollutants into the larger system. By breaking down the larger watershed into these manageable units, the CANALPY model facilitates tailored interventions, grassroots participation, and the establishment of governance structures with clearly defined roles and responsibilities. This localised approach ensures interventions meet the unique needs and conditions of each area, promoting effective and sustainable pollution management.

Central to the CANALPY model is the emphasis on Local Self-Governance Institutions (LSGIs), which serve as pivotal points for action and engage actors across various governance levels. This focus on LSGIs enables replicability to other Urban Local Bodies (ULBs), thereby enhancing its potential impact.

However, while the CANALPY model addresses significant aspects of pollution management, it is not a comprehensive solution for all challenges facing Vembanad Lake. Industrial and agricultural pollution, in particular, require interventions at higher governance levels beyond the model’s scope. Thus, additional strategies targeting these pollutants are crucial to ensure the long-term sustainability of the lake.

Authors

Prof. NC. Narayanan

Head, ADCPS,

IIT Bombay

Rohit Joseph

Managing Director,

Tags Forum

Sruthi Pillai

Director,

Tags Forum

Navya Cathareen

Project Head

TAGS Forum

Ashitha Tharian

Project Head

Tags Forum

Safeeda Hameed

Reasearch fellow,

Tags Forum

Joseph Thomas

Research Assistant,

TAGS Forum

Illustrations