A nature-based solution for Kuttanad’s flood mitigation

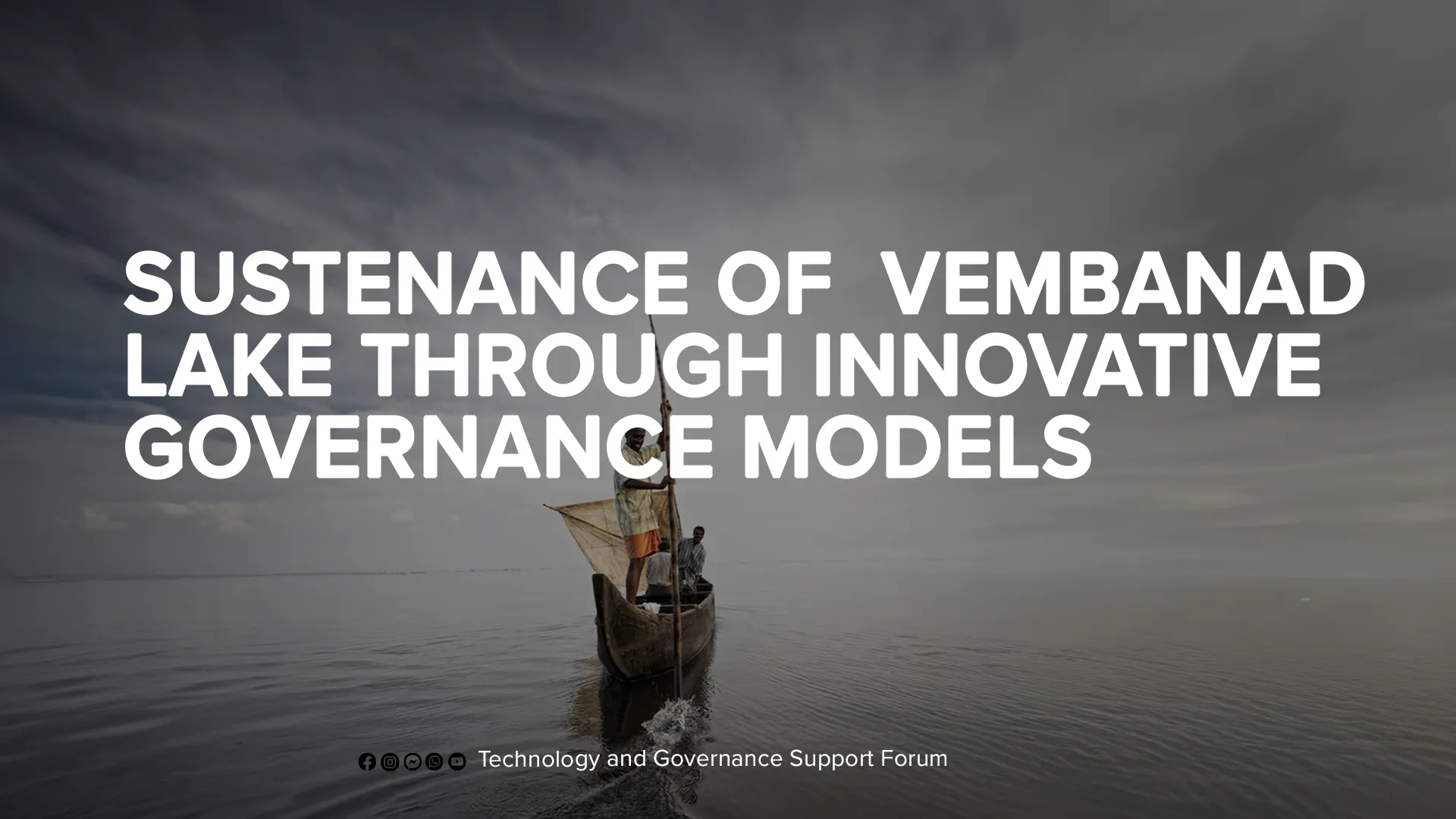

Kuttanad is a deltaic region and includes the Vembanad lake, one of India’s well-known Ramsar sites. This region, home to approximately 2 lakh people, has been in the global spotlight due to recurring floods that have caused significant damage and displacement. The floods have been a major topic of discussion in Kuttanad and can potentially have a decisive impact on political developments in the region.

2018 Flood Aerial View of Kuttanad

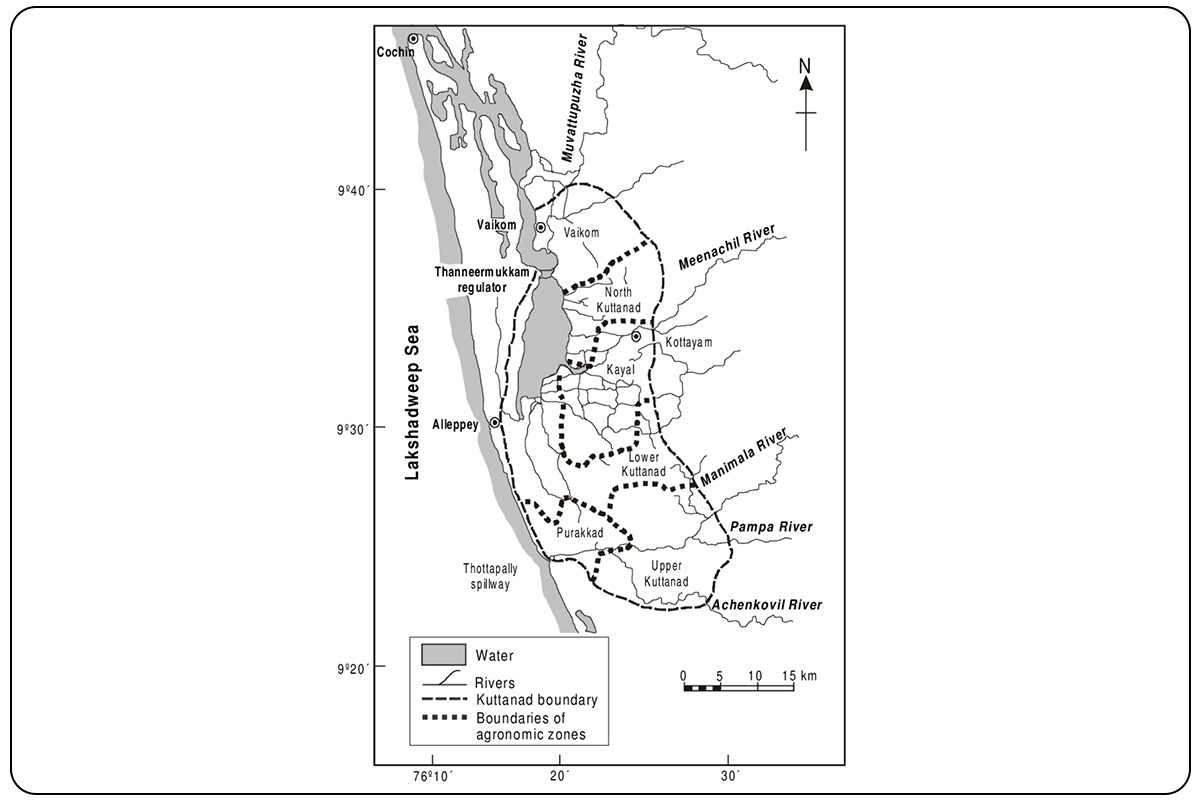

Geographically, Kuttanad is a part of the deltaic system of the Vembanad wetland, where five rivers originating in the Western Ghats flow before emptying into the Arabian Sea. The region has been divided into six zones, taking into account its agro-climatic characteristics. Among these zones, Upper Kuttanad, Purakkad Kari, Northern Kuttanad, and Vaikom Kari, which are at a relatively high elevation, have an area of 29193 hectares and are prone to floods caused by the overflow of major rivers.

Kuttand taluk map

On the other hand, Lower Kuttanad and Kayal Nilams, covering an area of about 25744 hectares and located 1-2 m below the mean sea level, are regularly affected by floods due to progressive silt deposition and declining carrying capacity of the water bodies. Vembanad Lake is unable to accommodate incoming waters from rivers and tidal incursions from the sea. Floods often occur when the bunds collapse at high tide, and the resulting inundation of floods due to lack of drainage can last for months.

Climate change has dramatically increased the flood risk in Lower Kuttanad and Kayal Nilams, making it essential to adopt measures to mitigate the risks. In this article, we will discuss an approach adopted to mitigate flood risk in this region.

The water system in KuttanadThe water system in Kuttanad

Kuttanad, a region in the Vembanad wetland complex, is known for its unique water system. The Vembanad wetland system is a combination of rivers, lower-order streams, and human-made canals. The streams and canals that flow into the paddy fields play a significant role in determining the flood potential of the lower Kuttanad and lowermost Kayal Nilams. Since the land here is below the level of the rivers, water constantly flows from rivers into the streams and then into the paddy fields. To protect the paddy fields and settlements inside from flooding, bunds, or embankments, have been constructed around them, creating a shield against the rising water levels. The consequences of bund failure can be severe, causing damage to life, livelihoods and infrastructure like houses built around the bunds and sometimes inside the paddy fields. To prevent this, the bunds must be regularly maintained and restored if they collapse. During times of flooding, pumping is the only option to drain water, as the area is below sea level, and the water that enters cannot flow out.

Paddy Fields Flooded from Bund Breach

Bund Breach in Lower Kuttanad

The Lower Kuttanad and Kayal Nilams in Kerala, India, is facing a significant challenge due to the silt and clay deposits carried by rivers from upstream. These deposits are reducing the capacity of water bodies in the region every year.

Hammering coconut poles and fencing

The traditional practice in Kuttanad was to constantly rebuild the bunds by retrieving clay from the water bodies. This process has two advantages: it increases the carrying capacity of the water bodies, and it strengthens the bunds. In the past, when the feudal system prevailed in the region, the availability of cheap labour made it easy to construct these bunds using clay. After land reforms, when labour became expensive and to overcome this challenge, there emerged masonry bunds with the help of the state.

Collection of river sludge for traditional bund construction

Civil engineering technology has made significant contributions by introducing stone, earth, and concrete as raw materials for bund construction. An increase in transport facilities helped stones from the Western Ghats and sand from rivers to make stone bunds. However, even these bunds have not been entirely immune to changes caused by water and living organisms, and many of them have broken in recent years, causing flooding in the paddy fields.

The outer bund of the ‘C’ Block in Kuttanad being constructed using pile-and-slab method

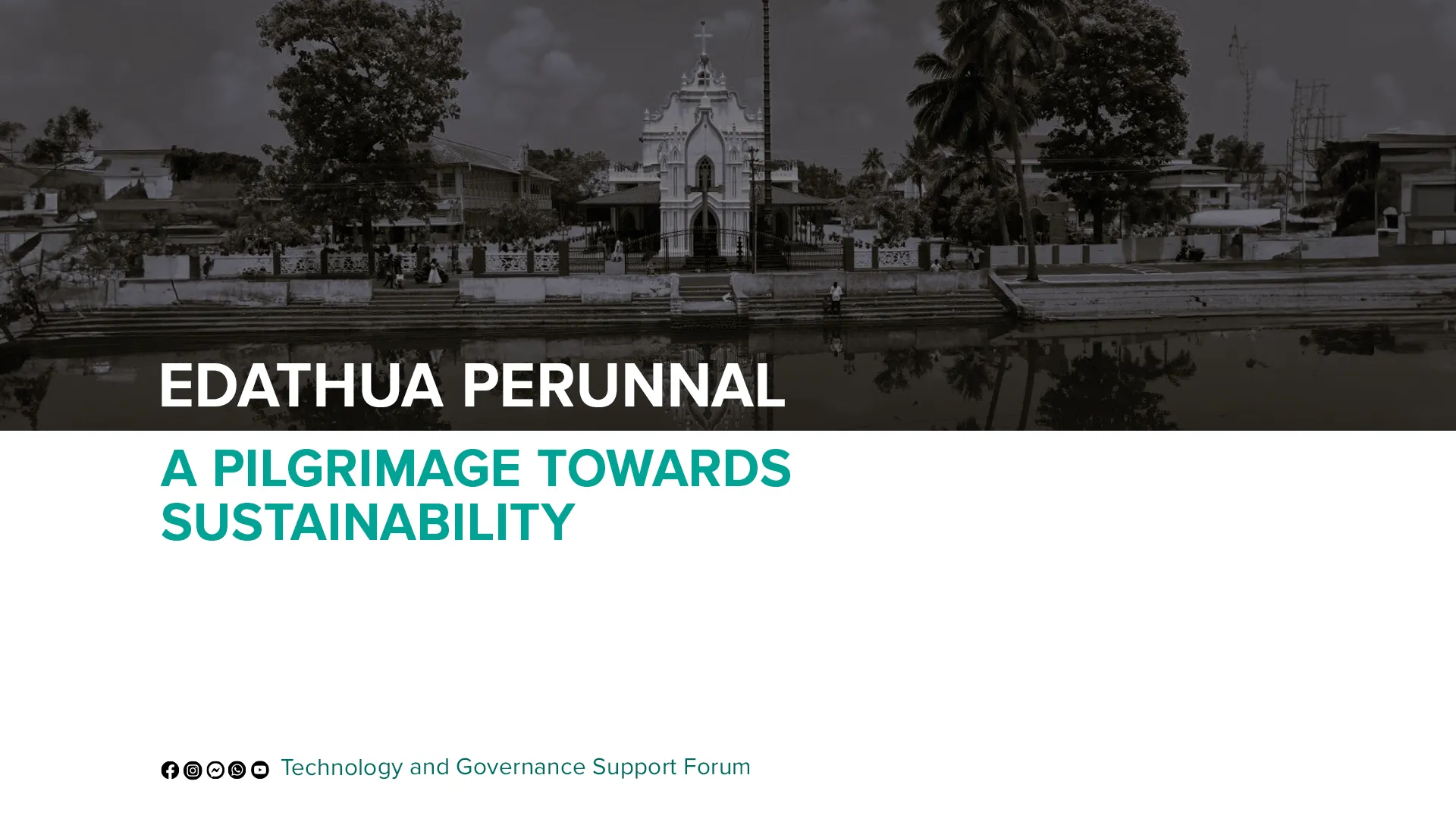

Thumpuram Project-An Opportunity

The Thumpuram project aimed to develop a sustainability-focused intervention for constructing bunds in Kuttanad. This was done with the assistance of IIT Bombay’s living lab in Alleppey named CANALPY. This program was prepared under the joint auspices of various organisations, including Kerala State Coir Corporation, National Coir Research and Management Institute, local Engineering College, Champakulam Block Panchayat, and Nedumudi Gram Panchayat.

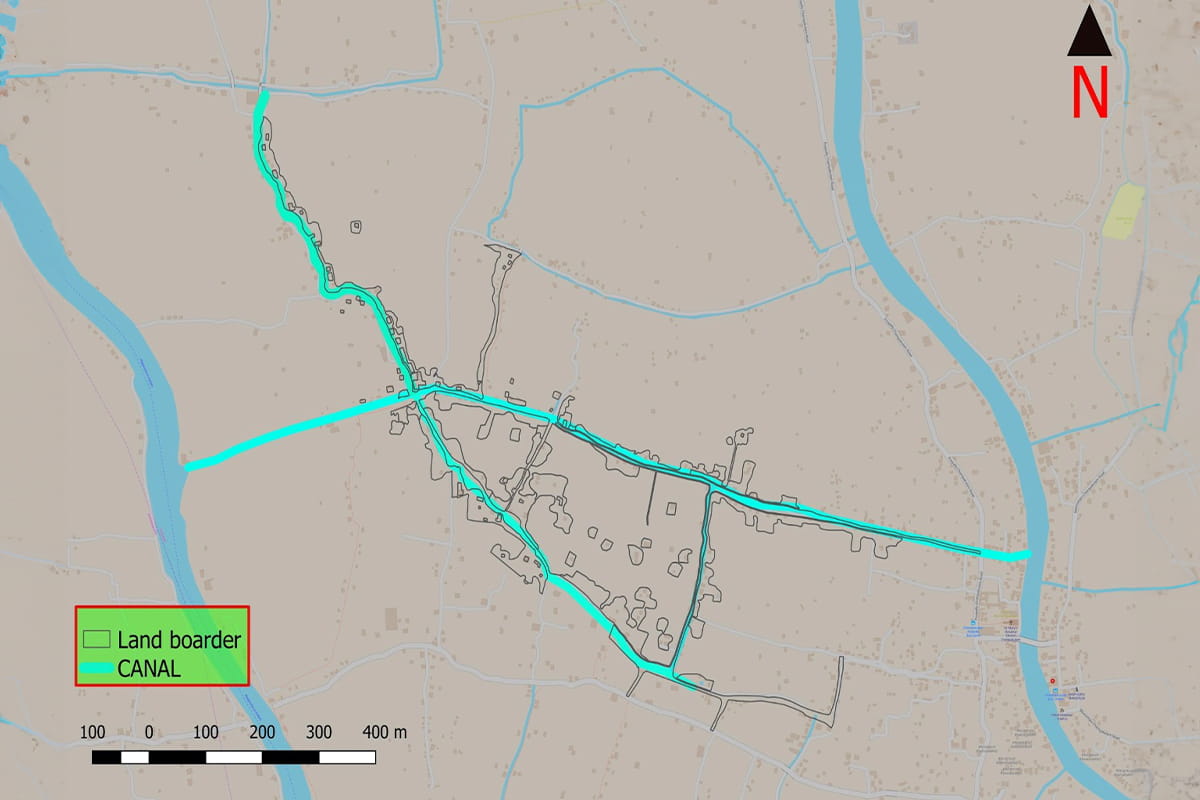

Graphical representation of Thumpuram Paddy field

The first phase of the project involved a detailed canal survey by civil engineers from CANALPY, which helped determine the depth and width of the canal and the amount of clay and weeds to be removed.

Civil Engineers Conducting Detailed Canal Survey

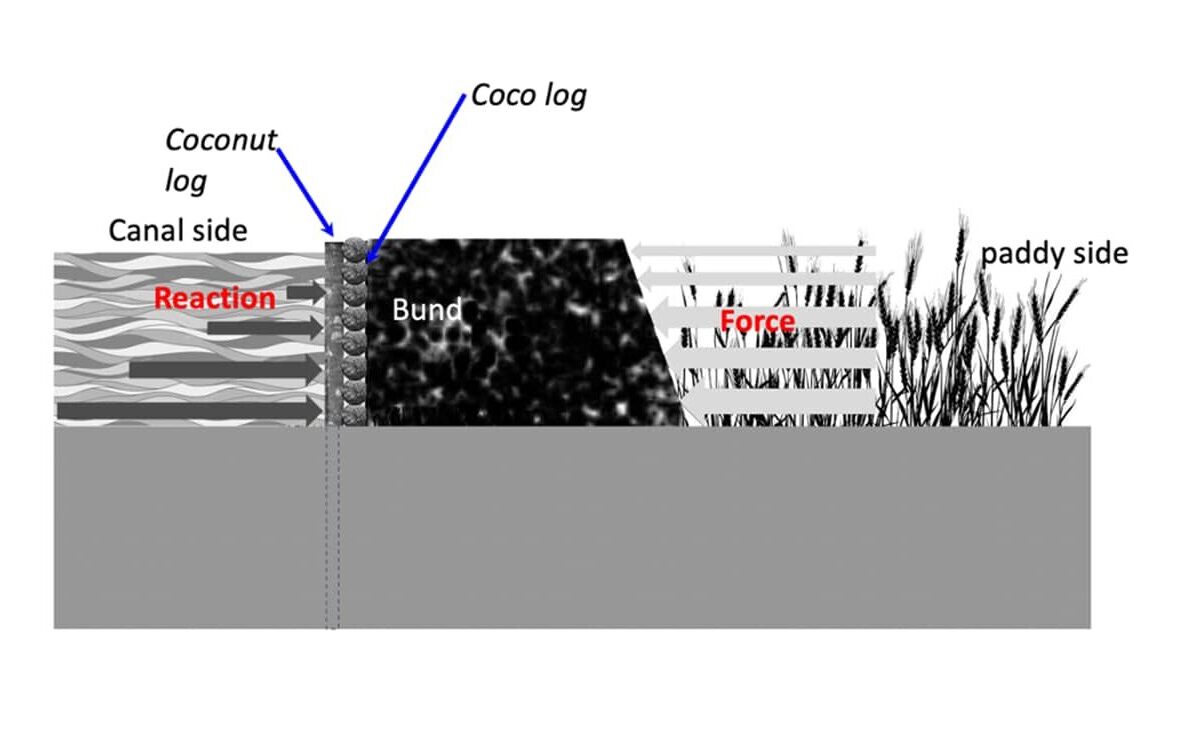

Then the design to construct a bio bund using the removed clay was carried out under the guidance of the local engineering College and NRCMI. The design involved constructing a strong bio bund using locally available clay, coir fiber, and coconut wood. The cost of these materials was much less than that of stone bunds. To ensure the strength of the bund, geotextiles were placed as reinforcement between each layer of clay, and long coconut stumps and coco logs were outside the bund. The construction of the bund required a significant amount of manpower, which was mobilised from the Centrally funded scheme MGNREGA. The project was initially planned to be completed in three months, but due to the spread of covid and the lockdown, it took eight months to finish the project.

Schematic diagram of coco log installation

Despite the delay, the Thumpuram project has been a success and is still functioning without any problems. The project not only restored the flow of canals and constructed a strong bio bund but also provided a sustainable model for other similar flood-prone areas. The use of locally available materials and the mobilisation of manpower from the MGNREGA scheme helped keep the costs low while ensuring the strength and sustainability of the bund. The Thumpuram project is an excellent example of how sustainability-focused programs can contribute to the restoration of water bodies and the development of flood-prone areas.

Process involved

Weed Removal

Excavation of Clay

Clay distribution

Bund making with geotextile composite

Bund Strengthening using coconut wood and coco logs

Stone bunds vs. bio-bunds

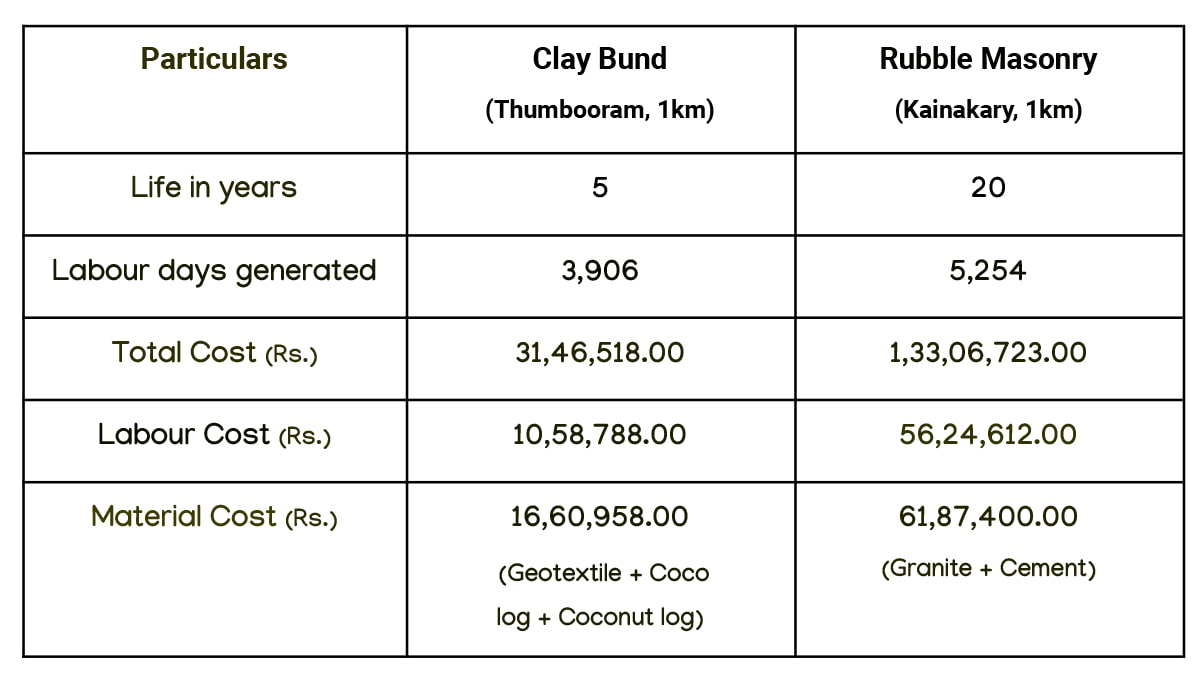

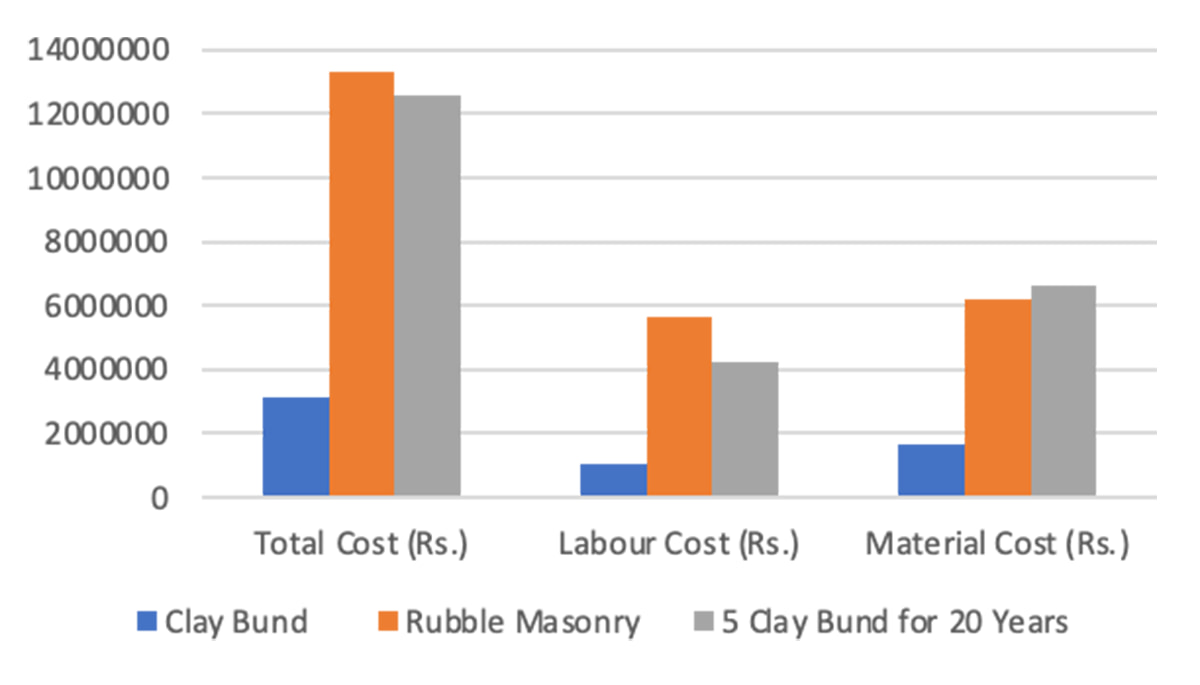

There is a significant difference in construction cost and durability between bio-bunds and stone bunds. While the maximum lifespan of a stone bund is 20 years, it costs around 1.4 lakh rupees to build one kilometre of stone bund. In contrast, the lifespan of a bio bund is only five years, but the construction cost is only one-fifth of the stone bund’s cost. Therefore, building bio-bunds every five years is a cost-effective solution that eliminates the need for spending large sums of money on tying stones for 20 years.

Graphical representation of Thumpuram Paddy field

Another critical advantage of building bio-bunds every five years is that they allow for the removal of clay from water bodies, a necessary step to maintain their strength. Stone bunds prevent the deepening of water bodies, and once constructed, the water bodies cannot be deepened without causing the bunds to collapse. However, by constructing bio-bunds every five years, it is possible to restore the depth of water bodies and utilise the excavated clay for bund construction, significantly reducing the risk of flooding in the area.

Stone bunds also require a great deal of maintenance and repeated rebuilding due to natural decay and damage from aquatic organisms such as fish, snakes, and rodents. In contrast, rebuilding and constructing bio-bunds every five years is a better option, considering that nature and living things constantly reduce the strength of stone bunds.

Graphical representation of Comparison between clay bund and stone bund

The raw materials required for building stone bunds, including rock, cement, and soil, are unavailable in Kuttanad and must be brought from outside. However, the raw materials required for bio-bunds, including clay, coconut fibre, and coconut wood, are readily available in the region, making the process more accessible and cost-effective.

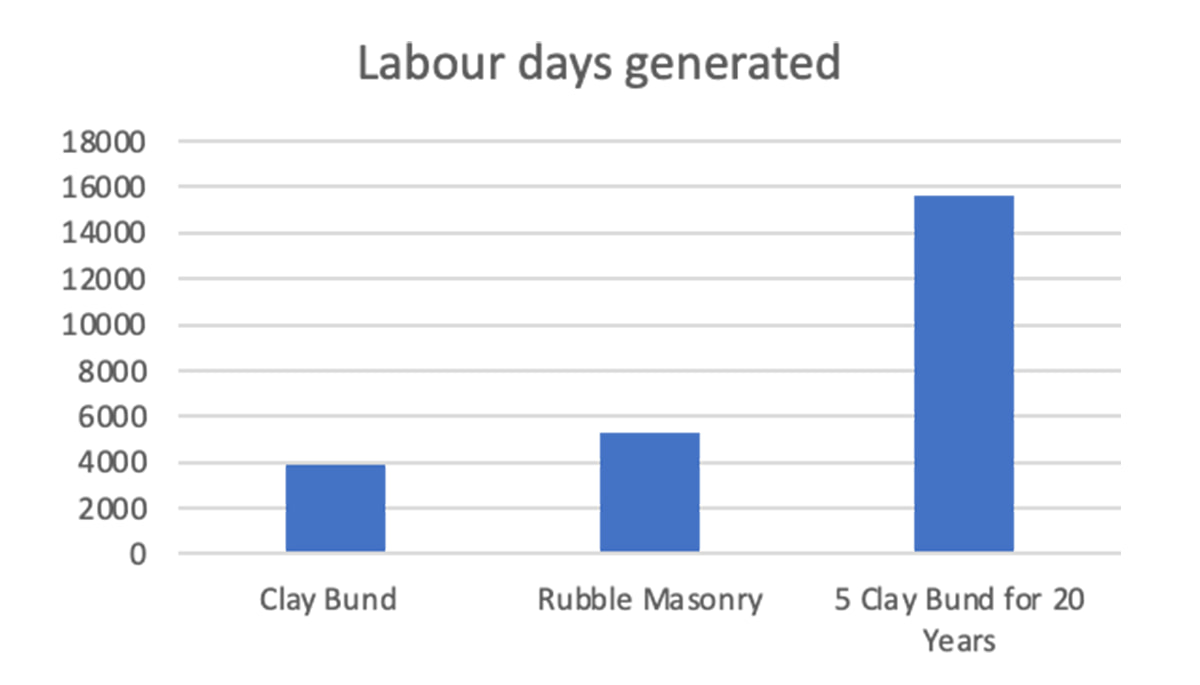

Lastly, the employment potential of bio-bunds is much better compared to stone bunds. Building a 20-year stone bund requires the services of about 5,000 workers, while constructing a five-year-old bio bund takes 3,500 labour days. But, building four bio-bunds for 20 years would require around 14,000 labour days, which can be sourced through the MGNREGA program. Thus, this method provides maximum employment opportunities for women workers.

Graphical representation of man-days generated during the clay and stone bund construction

Discussion

Bio-bunds have the potential to be a viable solution for sustainability challenges in Kuttanad, particularly in areas where traditional stone bunds are not feasible. While we don’t argue that bio-bunds are a replacement for stone bunds in the entire region, they are a valuable option wherever possible.

One of the key advantages of bio-bunds is their ability to maintain the carrying capacity of water bodies by reducing resource exploitation from the Western Ghats and slim rivers of Kerala. This is especially important in Kuttanad, which is vulnerable to floods and soil erosion. By constructing bio-bunds at potential sites, we can help mitigate these issues and ensure the long-term health of the region’s water bodies.

Another important benefit of bio-bunds is their potential to generate local employment opportunities through the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). Women workers in the region can particularly benefit from this approach by earning maximum wages and contributing to the sustainable development of their communities.

While the potential of bio-bunds is clear, more applications and studies are needed to spread these activities throughout Kuttanad. This will require process innovations and capacity development programs that can help institutionalize bio-bund projects as part of Panchayat and MGNREGA initiatives. Under the leadership of IIT Bombay, the Living Lab has conducted a workshop for gram panchayats in collaboration with the District Panchayat to explain the potential of building bio bunds. This is administratively also easie since MGNREGA planning and local labour mobilisation with local design capabilities can be planned by gram panchayats without the overt dependence (and covert corruption) of line departments like irrigation. The CANALPY team with local expertise is currently working to fulfill this need by providing technical expertise and support for bio-bund projects in the region. In conclusion, the potential benefits of bio-bunds are sustainable natural resource management, employment opportunities for local communities, and mitigation of the effects of climate change in the region.

Authors

Prof.N. C. Narayanan

Head of Department, Ashank Desai Center for Policy Studies, IIT Bombay